Intro:

What is it that we mean when we say surveillance? The word itself evokes thoughts of George Orwell and Big Brother, but it’s easy to convince ourselves that we don’t always think of surveillance so negatively. What of the shopkeeper who wishes to reduce theft with security cameras? The taxi driver whose dash camera prevents insurance fraud? Is not the daycare worker who watches over a group of young children necessarily performing surveillance? And further isn’t this a form of surveillance that we necessarily endorse? These aren’t deep examples but they’re enough to lead us to a not so deep insight: surveillance is something we like in some contexts and dislike in others.

The examples I’ve provided are fairly one dimensional and we can easily distinguish what it is that makes us like or dislike the surveillance in question. Obviously, the Orwellian surveillance of 1984 and the daycare worker watching a group of children are two very different things. But the distinction between surveillance we desire and surveillance we don’t need not always be so clear. For instance, one criticism of surveillance of the Orwellian sort might be that it is nonconsensuala. No citizen requested they be watched over for their own benefit, it occurs independent of their desires. However, in other contexts, this is something we as a society totally accept and even endorse (here I must state that I am writing for an American audience and thus will use examples from an American context).

Consider, the Social Security Administration assigns to every citizen a unique number used to track the money they earn in order to fund entitlements for the elderly. No-one born after the establishment of this program consents to this sort of tracking and, for most people, not paying into the program is illegal. Compliance with paying these entitlements is tracked intimately by a dedicated group and noncompliance is swiftly punished1. This example illustrates two things.

First, it shows that there is a degree of nuance between some of the differences amongst Orwell’s scenario and our present one. Certainly, we aren’t all openly being continuously audio and video recorded in our most private moments, but we rarely think about how organizations like the SSA and the IRS work. They hold the personal information of and gather data on a truly massive group of people, tracking this to ensure compliance with the established rules and laws of American society. When phrased this way, it is difficult to argue that these organizations aren’t on some level Orwellian (at least in a superficial way, more on this in a bit).

Second, it demonstrates that surveillance isn’t just watching someone or videotaping them. Routine, centralized data-gathering used for the purposes of record-keeping and ensuring compliance (like the IRS and SSA do) certainly seems like it ought to be considered a form of surveillance and it’s difficult to come up with a reasonable definition in which these organizations aren’t performing surveillance. Further, it seems this sort of centralized record-keeping is at least somewhat necessary for the function of society.

I’ve thus far avoided providing a definition of surveillance and in this article I won’t. Beyond whatever problems I may have with linguistic prescriptivism, I feel that defining surveillance explicitly will only serve to limit what we may think of as being surveillance. Further, I am no expert in the field of surveillance, and therefore I leave the task of specifically defining what we mean by surveillance to those more experienced in the field than myself. In this intro, I wish only to convey one main idea: using the word surveillance in the way we typically do, surveillance includes many more things than we typically think.

The teacher, who watches his students, observes all their various work, and assigns them a numerical value of how well he feels they did, is performing surveillance. The doctor, who observes her patient’s symptoms and behaviors, makes a diagnosis, and records this for later use both by herself and other doctors, is performing surveillance. The manager, who watches her workers and ensures their compliance in terms of quality and quantity of labor, is performing surveillance. It is not just the FBI agent or the night watchman nor is it just for crime deterrence or intelligence gathering. Surveillance is everywhere, in all parts of our society and all of us perform surveillance, have surveillance performed on us, or both in the course of our daily lives.

I’d like to be clear here that I don’t feel the IRS or SSA are Orwellian entities, which seems reasonable as most people don’t either. Sure, we can make it sound like these agencies are evil through scary buzz-phrases such as “centralized mass data-gathering”, but we seem to accept that they fulfill a necessary role. In general, centralized record-keeping of the sort performed by agencies like the SSA are a necessary part of any modern society. Surveillance scholar David Lyon concurs with this analysis in his book Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society, describing numerous historical societies going as far back as ancient Egypt that used centralized data-gathering and storage for the purposes of record-keeping and administration2.

Surveillance is an important part of any society, and every society performs some sort of surveillance to some extent or another. However, the degree to which we, the participants of society, accept surveillance, the degree to which we are interested in performing surveillance on one another, how personal and intimate the types of surveillance desired are, and many other such parameters are all variable. The values a given society may set for these various parameters is one way in which societies may differentiate themselves from one another. Of course, here I am simplifying. All of these values are in constant flux due to the various cultural and social forces that pressure them to change.

Gilles Deleuze, in an influential short essay titled “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, describes modern society in just this way, in what he calls a society of control3. The various societal parameters continuously modulate, changing in response to whatever diverse forces affect this change. As an example, we can see how these variables were momentously tweaked in response to 9/11. In an instant, the degree to which our society expects surveillance, the degree to which we accept it as necessary, who and how we want surveilled, the nature of the surveillance we want, all shifted instantaneously. We now know that this modulation of our societal parameters also affected us in unseen ways, such as in the NSA surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden. In a society of control, modulations like these (and of course, many others) actively affect how we live, what we do, where we go. They fundamentally define society.

The focus of this article is the discussion of the (as of its writing) ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and how it relates to issues of surveillance. What techniques have been used to surveil COVID-19? How have different surveillance societies responded to the pandemic? How might COVID-19, like 9/11, momentously modulate the societal parameters of surveillance? I’ll seek to shed some light on some of these questions.

COVID Surveillance:

Before I begin, I’d just like to make a little editorial note here that I won’t be distinguishing between the virus SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, Coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19. If this sort of thing annoys you, be warned.

First things first, let’s talk surveillance techniques. Many different organizations have used many different methods of surveillance in response to the pandemic and I’ll be listing and discussing a few of them in the paragraphs below.

Testing:

I’d like to note that there exist multitudes of different forms of COVID testing of many different types, efficacies, reporting times, etc. These will go mostly undiscussed in this article. Instead I will be focusing on two types of COVID-19 test: the virus test and the antibody test. By the virus test I mean any sort of test that determines whether a person currently has the coronavirus and by the antibody test I mean any sort of test that determines whether a person has had the coronavirus before (this is especially important given that a significant portion of coronavirus cases are mostly or entirely asymptomatic). Of course, I’m simplifying here but these two definitions are sufficient for the purposes of this article.

Virus Testing:

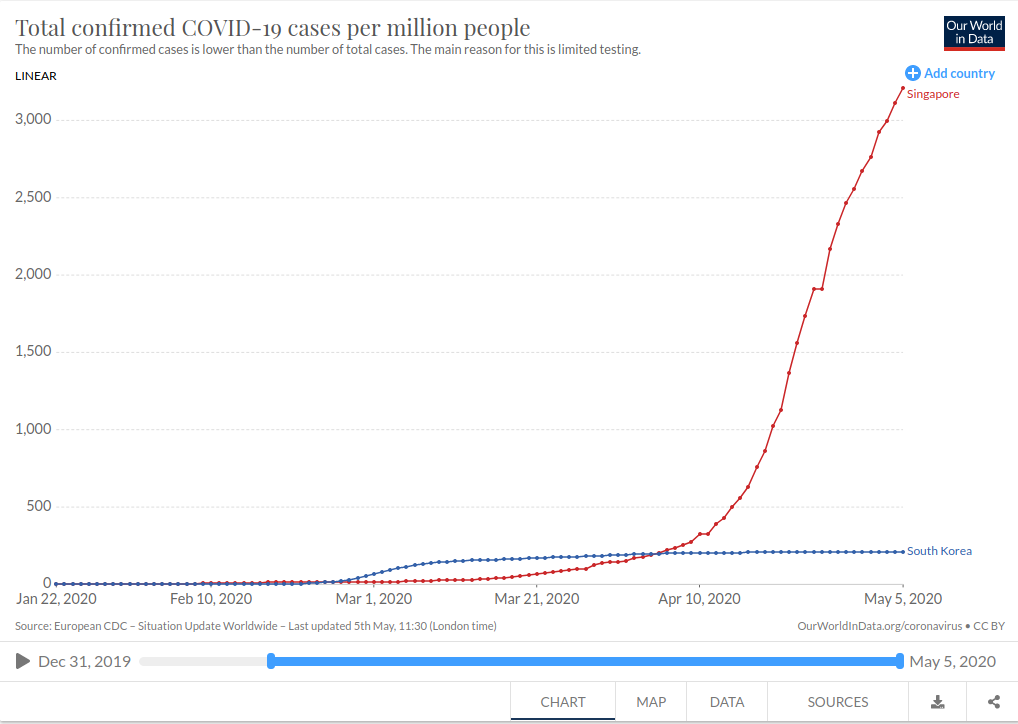

General availability of coronavirus testing appears to be one of the most significant determining factors of the efficacy of a given country’s COVID-19 response. To demonstrate, compare the testing programs of South Korea and Singaporeb.

South Korea implemented a centralized testing system, with walk-in clinics allowing the general populace to be tested (either for free or at little cost) in under half an hour. The South Korean government also provided quarantine stimulus packages, giving masks and gloves to those who tested positive, and ensuring that anyone stuck in quarantine has sufficient food and financial resources to survive4.

Singapore implemented an aggressive contact-tracing system (more on contact-tracing and the Singaporean response later) that liberally allowed doctors to test any patient they suspected of having coronavirus5. Given that Singapore has universal healthcare, this made it easy for anyone who suspected themselves of being sick to get testing if desired.

What’s significant is how effective the different testing systems were. South Korea has effectively halted the virus whereas Singapore, despite initial successes, has failed to contain it (as of May 10th, at least). Currently Singapore has around twice as many confirmed cases as South Korea with this differential expected to increase (South Korea has close to 9 times as many people as Singapore for reference)6. Both had testing programs that allowed the general populace to be tested if a doctor deemed it worthy. South Korea succeeded. Singapore failed. Why?

The failure of the Singaporean response seems to hinge upon its failure to test its large migrant worker communities, who mostly live in rather poor, cramped dormitories. Though initially successful, the virus crept into these communities where testing was less prevalent and aggressively grew, unseen and unchecked8. This seems to indicate a failure of the testing system, one where a bias towards testing a certain population significantly affected its overall efficacy.

Surveillance scholar Oscar Gandy has written extensively on such phenomenon. In an excerpt from his book The Panoptic Sort, Gandy describes a credit evaluation system developed by the Spiegel corporation in 1934 used to assess credit applications. The system evaluated applicants on several different criteria which included things like occupation but also things like their race. In the modern day we can recognize this as a flaw of the system, both morally and factually. Gandy contextualizes this sort of system in a general sorting process he refers to as the panoptic sort, which is used to classify various members of society. Importantly, Gandy states the panoptic sort in and of itself is neither good or bad but is affected by the biases and prejudices of the surrounding society, like how the Spiegel system was biased against colored applicants7.

The failure of Singaporean testing system can be seen as a modern example of this phenomenon. The migrant worker communities of Singapore are relatively poor and downtrodden, with no minimum wage guaranteed for migrant workers and most of them living in cramped dormitories as temporary laborers5. The biases of Singaporean society against this group seeped into their central testing apparatus and as a result it failed to properly classify various sick migrant workers as sick. I’ve focused exclusively on two countries in Southeast Asia, but this idea of the panoptic sort generalizes. It isn’t difficult to see similar failures in countries such as Brazil and Bolivia. I encourage the reader to try and think about surveillance in these terms, to think about how a surveillance apparatus such as a testing system may have failed due to the biases of the society it is implemented in. It provides a solid basis to not only understand and improve these systems, but also to critique them where they fail and praise them where they succeed.

Antibody testing:

Antibody testing is a form of COVID-19 testing that allows medical personnel to determine if a subject has developed antibodies for the coronavirus (and therefore if the person has been infected by the virus at some point in the past). This sort of testing is essential for understanding the spread of coronavirus as there have been numerous reports that a significant portion of the population can carry the virus while showing little to no symptoms8. This information is important to practices like contact tracing but has really only been implemented recently due to the fact that antibody testing isn’t an essential part of an initial COVID-19 response (antibody testing isn’t essential for diagnosing active cases, which is the primary focus of any initial response). This also means that there isn’t a lot of data on how countries have used antibody testing practically or as a means of surveillance, which mostly limits me to theoretical discussions and speculation. I’ll try to limit my predictions of the future but there are a few things I would like to discuss.

The WHO has warned against the use of something like an “immunity passport”c, at least until we better understand the virus9. It is worth noting that whether or not someone has coronavirus antibodies fits nicely as just another portion of the identity of an individual in modern mass society. To French philosopher Michael Foucault, the body is the central object of all politics. Given an additional parameter by which to understand and further classify the individual, what sort of mass sorting apparatuses might be used in response to the pandemic? Can we expect, in the near future, antibody presence to be necessary for certain people to return to their jobs? Given the potential long-term effects of contracting coronavirus, how can we expect the medical community to track and record those of us who have contracted the virus? How might an individual respond to the knowledge that they unknowingly spread the virus? What other long-term effects might coronavirus antibody testing have? I’m afraid I have the answer to none of these questions, and only wish to say that they’re certainly worth asking and considering.

It’s not currently clear how effective something like an immunity passport might be, but the desire many organizations currently have for something of the sort is undeniable. Numerous entities, countries and private companies alike, have already implemented something approaching an “immunity passport” in the form of body temperature checks. Be it at airports, before entering shops or government buildings, or prior to crossing a border, quite a surprising number of places require a normal body temperature to perform various daily activities10. This is an interesting instance of social sorting in itself, but it’s even more interesting given that the WHO has stated such checks are ineffective for a number of reasons.

It’s difficult to accurately attain body temperature with just an external thermometer, and even given an accurate temperature reading, an abnormal body temperature doesn’t necessarily indicate the presence of coronavirus11. It’s easy to see that temperature checking is rather poor at distinguishing sick from healthy, and yet so many have readily adopted it. Based on this, I wouldn’t be surprised if a significant number of organizations began using antibody testing credentials to ascertain the health of their patrons, regardless of WHO recommendations. Naturally an antibody test lacks the convenience of a temperature check and this may make it inviable for smaller operations, but as for airports or border stations such a check is far from unreasonable. What does this mean for the future? It’s truly hard to say. Only time will tell.

Contact Tracing:

One of the most prominent forms of surveillance used against COVID-19 is contact tracing. Contact tracing, in short, is the monitoring and tracing of infected individuals. It is used to understand how a disease has spread and where a disease might spread next, both useful things to know when responding to a pandemic12. Traditional contact tracing means testing the infected, interviewing them, and contacting those they may have infected. Naturally, digital solutions have become more popular in the modern era. I will discuss both.

I’ve previously mentioned Singapore implemented an aggressive contact tracing program, one that I’ll discuss more here. Through its testing programs, Singapore (initially) did well to understand how the virus had spread and where it may go next. Though they recently rolled out a digital contact tracing app, Singaporean health ministers have doubted the efficacy of digital contact tracing systems13 and have mostly relied on traditional contact tracing methods in order to track the virusd. Of course, neither solution was sufficient due to systemic biases of the Singaporean testing apparatus, as we previously discussed.

This does present an interesting question, however. How might the efficacy of a digital contact tracing system differ from that of a traditional one? Enter China. China, of course, is the country of origin for COVID-19, meaning that we might expect a very poor initial response exclusively because the virus had never been seen before. Indeed, this is what we saw, but the Chinese found themselves in a fairly unique position in terms of implementing a digital tracing solution. Most Chinese citizens own a smartphone and, because the government of China censors various apps Western users are familiar with, most of those who own a smartphone use one of a handful of government-developed apps (messaging, search engines, smart pay, the like)14. This meant that the Chinese government could ensure large portions of the population could be digitally contact traced in a way that the Singaporeans couldn’t.

The Chinese government took full advantage of this, requiring users of these apps to fill out a survey which included questions about where they had traveled, their medical information, and their national registration information. From this info, the government sorted citizens into three colored categories. Green for the least likely to contract the virus, red for the most, and yellow for those in the middle. During lockdown, the government required citizens to show their color code to guards at various locations in order to go about their daily businesses. Only those with a green color code would be permitted to perform these activities, with those in the yellow and red categories forced to stay home. The government would provide for their various needs while they were in quarantine.

It’s notable that this intense digital contact tracing program was incredibly effective, with the Chinese flattening the curve and eventually lifting the lockdown orders6. Deleuze describes this sort of sorting as a “dividual” process, one that is continuously modulated just like the various social parameters from before. Control is exhibited on the individual by changing what various parts of the city they may or may not have access to in a scheme that is continuously in flux. In describing dividual processes, Deleuze draws off a scenario presented by his long-time collaborator Felix Guattari that eerily mirrors the Chinese situation. Guattari imagines a city that individuals are granted access to the various sections of based on (dividual) cards each one carries. Of course, the powers that be may decide to only grant this access at certain times or on certain days, but what is truly important is that this mechanism of control exists in the first place, perfectly mirroring the Chinese situation. This social sorting that controls how an individual participates in society based on continuously modulating parameters is exactly what Deleuze means when he describes a society of controle.

The Societal Implications of COVID-19:

With this discussion of some of the surveillance techniques that have been used during the coronavirus pandemic and how we might understand them in the lens of some surveillance theorists out of the way, I’d like to turn our thoughts to the implications that coronavirus may have on the worldwide community. Will the coronavirus pandemic be a 9/11 like event in terms of how it shifts the social parameters related to surveillance? Of course, it’s difficult to say given that the pandemic is far from over, but ‘probably’ seems to be the most reasonable answer.

Purely in terms of how we’ve understood the pandemic in terms of Deleuze’s ideas on societies of control, it seems very difficult to say that this won’t result in a shift of those societal parameters. The pandemic has been shocking and highly unprecedented. It has presented unpredictable challenges to our governments, our economies, and our healthcare systems. It has necessitated long periods of social isolation and reinvigorated tribal fears of out-groups. In a very fundamental way, it has made people distrustful of all those around them, living in constant paranoia of contracting a potentially deadly virus. Given the necessary cultural manifestations of these various shocks, it is difficult to say that there won’t be any modulation at all or that there will be a modulation towards less surveillance. The unique nature of the pandemic necessitates that the modulation be towards that of a stronger surveillance system.

These changes have already been observed. A primary concern of many surveillance scholars is in how location data has been used to track COVID-19, and how this might set a precedent for the use of this data after the pandemic’s end. Such datasets have been collected by countries and private firms alike15. It’s not clear how the collected location data may be used in the future, and further who may want to obtain this data and for what purposes.

An important dimension to this discussion of GPS data being used for contact tracing is that GPS is insufficiently accurate to determine whether two people had close enough contact to transmit the virus. Current CDC guidelines state that a 6 feet distance minimum ought to be kept in order to stunt the spread of coronavirus16, though some guidelines state that this ought to be as much as 10 feet17. In contrast, current GPS standards indicate that the system is accurate to within about 26 feet 95% of the time in ideal conditions18. This confidence interval worsens even further in non-ideal conditions, such as when a user walks under a bridge or in a tunnel. Clearly this is too inaccurate to perform effective individual contact tracing, and yet many countries have used this sort of tracking as a cornerstone of the coronavirus responses.

It’s hard not to worry about this sort of development and it’s even harder to say what the future may hold in terms of this surveillance, though speculation tends toward the bleak side. Deleuze, for his part, ends his essay in a section where he speculates how those most vulnerable may rise to meet the challenges of this new sort of society. He compares the new society of control to a snake, ending bleakly with “the coils of a serpent are even more complex than the burrows of a molehill.”f How we may respond to these novel changes is wholly in our control, but what our response ought to look like is not for me to say. I wish only to convey that the current pandemic is almost certainly a pivotal event, one which will affect all of us for decades to come. We’re living history, let’s all try to make something of it.

Footnotes

a. Of course there are many criticisms beyond this, I only use it to illustrate a point.

b. I chose this comparison as both are relatively wealthy nations in Southeast Asia. It’s worth noting that the per capita GDP of Singapore is almost twice that of South Korea, but this isn’t particularly important here. Both nations are modern and industrial with enough wealth for a central coronavirus response. They’re also both relatively secure in terms of border transit, as Singapore is an island and South Korea borders just North Korea, a border along which I don’t imagine much border transit is occurring.

c. Presumably this passport would be something like a credential that someone could present to demonstrate that they have COVID-19 antibodies and therefore are immune to the disease, similar to how immunization records are used.

d. The app wasn’t nearly as popular as it needed to be to effectively contact trace. Only about 1 in 6 of those living in the country downloaded it.

e. I’d like to note that Deleuze doesn’t think that it is just societies like China that are societies of control, but rather basically EVERY modern society is a society of control. It just so happens that Guattari’s example is eerily identical to something that occurred in the modern day, which makes it a nice way to illustrate how contact tracing fits into a society of control.

f. In his essay Deleuze is comparing how new societies of control differ from the old sort of society that Foucault talked about, known as disciplinary societies. the animal mascot of which he states is the mole (hence his ending line). I’d like to note that I have extremely simplified Deleuze’s essay for my purposes here, and have left completely undiscussed many of the aspects of societies of control and why they necessarily present new challenges to those living under them.

Sources

- https://www.ssa.gov/ (simple overview of basic facts about the Social Security Administration)

- Lyon, David. Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society ch.2 “Surveillance in Modern Society” pp.33-50 1994. University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles. “Postscript on the Societies of Control” Pourparlers, Paris, 1990. Columbia University Press. (This article essay was originally published in French in L’Autre, an English translation I used can be found online here: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/gilles-deleuze-postscript-on-the-societies-of-control)

- https://abcnews.go.com/Health/trust-testing-tracing-south-korea-succeeded-us-stumbled/story?id=70433504 (ABC source on basic facts of South Korean COVID-19 response, not used for any of its differential analysis of the United States vs South Korea responses)

- https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/05/03/849135036/singapore-was-a-shining-star-in-covid-control-until-it-wasnt (NPR source on nature of Singaporean response and Singaporean migrant worker communities, not used for any of its numbers on infection or any of its analysis)

- https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases (I use this source for up to date COVID-19 numbers, note how in early May the difference in number of cases as well as the difference in steepness between the graphs of South Korea and Singapore)

- Gandy, Oscar H. The Panoptic Sort: A Political Economy of Personal Information. (The portion I I use is an excerpt I found in Surveillance Studies: A Reader by Torin Monahan and David Wood)

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/03/31/824155179/cdc-director-on-models-for-the-months-to-come-this-virus-is-going-to-be-with-us (WABE interview with CDC director Robert Redfield, lots of info here but I use the portion of the interview where he states that as many as 25% of cases are asymptomatic)

- https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/immunity-passports-in-the-context-of-covid-19

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/coronavirus-temperature-screening/2020/03/14/24185be0-6563-11ea-912d-d98032ec8e25_story.html (Washington Post story on countries using COVID-19 temperature checks, I use it as a source for the fact that many places are doing the checks and use none of its explanation or analysis)

- https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/updated-who-recommendations-for-international-traffic-in-relation-to-covid-19-outbreak

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/open-america/contact-tracing.html (CDC source, used for basic facts on what contact tracing is)

- https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/coronavirus-tough-decisions-painful-but-necessary-to-save-lives-says-lawrence-wong (Interview a Singaporean newspaper did with Lawrence Wong, a co-chair of Singapore’s coronavirus task force, I use the portion where he talks about the contact tracing app Singapore developed)

- https://fortune.com/2020/04/20/china-coronavirus-tracking-apps-color-codes-covid-19-alibaba-tencent-baidu/ (Fortune article on the Chinese COVID-19 response, discusses their color coding system and ‘ubiquitous payment, messaging, or search engine platforms’)

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/04/covid-19-surveillance-threat-to-your-rights/ (Amnesty International article on the threats of COVID-19 surveillance, note that number of countries that have implemented location tracking)

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html (CDC social distancing guidelines)

- https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-six-feet-enough-social-distancing.html (Livescience interview with Krys Johnson, an epidemiologist at Temple University, who states that the guideline ought to be as high as 10. From what I’ve seen the safe social distancing distance is a point of contention among experts. The WHO, for their part, say only 3 feet and I’ve seen sources go as high as 26 feet due to how far coronavirus droplets can travel)

- https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ato/service_units/techops/navservices/gnss/waas/benefits/ (This number from the FAA describes a particular GPS technology called WAAS, different technologies have different accuracies but none accurate enough for contact tracing, as noted above)