Meet the audio interview!

Introduction

I began this year and entered my formal study of surveillance culture with an open mind and many preconceived notions about what surveillance is, how it works, who uses it, and for what means. I carried a vague understanding that surveillance had something to do with power, but the specifics remained unarticulated. To me, surveillance came from “the Man”—the boss, the government, the police, the military, the big tech corporations, et cetera. Surveillance was sneaky and sinister—it was George Orwell’s “Big Brother” from 1984 and the NSA as exposed by Edward Snowden. It was the big guy keeping the little guy down, and as such, it was something to be resisted. While I had accepted that some surveillance was an inevitable consequence of modern life and its luxuries, this was just an unpleasant and unwanted side-effect to be tolerated. In the following months, while studying the work of surveillance-minded scholars such as David Lyon, Steven Nock, Torin Monahan, and Michel Foucault, I grew to discern limitations in my conceptualization of surveillance. During spring break in March, the COVID-19 pandemic was escalating quickly, and university classes were postponed and moved online. In the unfamiliar light of the pandemic, the limits of my former knowledge were laid bare before me. While it is understandably common to conceive of surveillance as restrictive, invasive, oppressive, and antithetical to personal freedom, that is not the whole story. Surveillance is something often sought and desired by individuals in the pursuit of personal freedom.

Surveillance vs. Personal Freedom

Professor of sociology and surveillance studies scholar David Lyon defines surveillance as “the focused, systematic and routine attention to personal details for purposes of influence, management, protection or direction.” To broaden a little and simplify, the essential mechanism of surveillance is the acquiring and collection of personal data for the purpose of influence or control. From this definition, it can be gathered that surveillance implies a power dynamic: the surveillant assumes the dominant position of power over the surveilled. Personal freedom refers to the ability for an individual to act without hindrance or restriction. It is agency over one’s own life—the capacity of self-determination. It would seem the concepts of surveillance and personal freedom are in direct conflict with each other, but in real-life application, their relationship is not so simply antagonistic.

In Pursuit of Increased Mobility

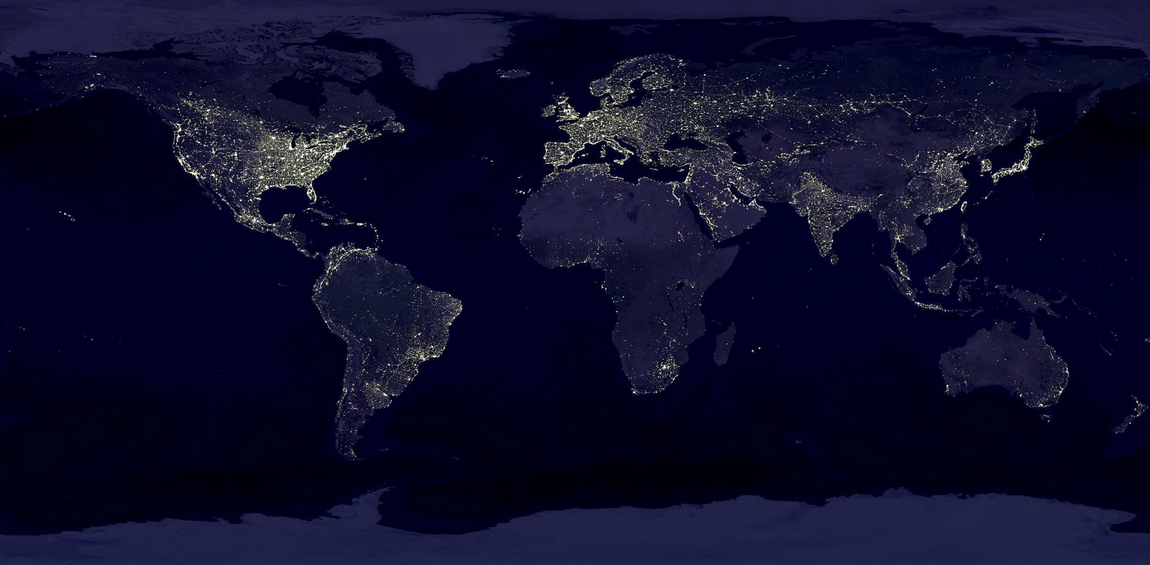

Steven Nock writes of how surveillance can afford us greater privacy and personal freedom. He points to the ways in which our society establishes trust and the reputation of individuals through use of credentials. He observes that in our increasingly large, interconnected, diffuse, mobile, and global society, we cannot rely on continuous, direct observation of others to establish trust. Therefore, to verify credibility we have incorporated the use of credentials such as identification cards, certification, licensing, and academic degrees into the complexity of our civilization. A COVID-19-related example of this would be use of the proposed ‘immunity cards’ to identify individuals who have been tested and confirmed to have developed immunity to the novel coronavirus. The card, a certificate of immunity, would be a credential that allows those who possess it greater freedom of mobility and the potential to seek or return to work while others are restricted. So, submission to the surveillance of being tested and registered as immune would result in an increase of personal freedom in terms of mobility. Whether this would be a net increase in freedom would depend on individual circumstances. I brought up the topic of the immunity certification cards with a few friends in casual pursuit of ethnographic data, and I was met with opposing views. “No way, that’s crazy!” was the response from TK, a retired Air Force veteran and children’s book author currently living in NYC. TK, who runs a small non-profit from home and whose primary income is in the form of military pension and disability benefits, views the immunity card proposal as an excuse for the government to expand surveillance practices and invade citizens’ privacy unnecessarily. TK’s roommate Tina feels differently. She doesn’t consider the proposal unreasonable, chiming in with “it’s not a bad idea.” It is important to note that Tina was recently laid off from her job as a hotel manager due to the pandemic. For TK, a homebody whose income is secure, the mobility restrictions resulting from the pandemic are inconvenient but not highly damaging to her lifestyle or livelihood. For Tina, a socialite who relies on her mobility for income, the restrictions are very damaging. She desires to restore the personal freedom she has lost and views the surveillance of the immunity cards as a means to that goal.

There is an important point to be made about the opposing views of TK and Tina: the same surveillance can mean vastly different things to different people. Prolific surveillance studies writer Torin Monahan criticizes the way Nock presents his theory that surveillance credentials replace interpersonal relations as the modern means of establishing trust. Monahan writes, “In Nock’s formulation, surveillance technologies simply automate social control functions that existed previously, without any other meaningful changes in social relations.” The introduction of immunity card surveillance would change social relations by establishing a new standard to be met by individuals who want or need increased mobility during social distancing orders. Attaining the card would require an individual to have had COVID-19 and to have access to proper testing in order to prove it. This would introduce two social inequities:

-

Individuals who have not had COVID-19 would be put at a disadvantage to those who have had it and recovered, with no regard to lack of infection potentially being due to following proper social distancing guidelines and regulations. This may seem trivial, but consider that the unemployment rate has skyrocketed—any leg up as we move toward reopening the country is going to be significant. There is reason to suspect that low risk individuals may be intentionally careless about contracting the disease. They could then verify their COVID-19 positive status and reenter the workforce, filling positions and leaving the more prudent behind. This would add undue strain to the healthcare system and increase the risk to more vulnerable populations. Furthermore, because those who are high risk need to follow prevention practices more strictly, they are already at a disadvantage to those who are lower risk. This surveillance measure would widen that gap further.

-

Individuals who cannot access proper testing to verify their immunity would be put at a disadvantage to those who can. We have seen for months now that the availability of proper COVID-19 testing in the United States is abysmal. High-profile government officials, celebrities, and the wealthy have ample access to testing while the rest are left wanting. Access to testing continues to (slowly) improve, but inexplicable scarcity sustains the conditions for judgment to be made as to who is and is not worthy of receiving a test. So it goes, those who are deemed more valuable to society are given priority when it comes to elective testing. The gatekeeping immunity card would reinforce and exacerbate preexisting inequalities.

Monahan continues his critique, writing, “(According to Nock,) as rational actors, each of us has evaluated the options and voluntarily chosen to participate in new surveillance regimes, seemingly without any coercion or without any sanctions if we had (somehow) chosen to opt out instead.” As shown by TK and Tina, different actors can hold different stakes in the same surveillance game. So, while it looks as though they are presented with the same hypothetical choice, in reality, Tina has less freedom of choice than TK because her livelihood relies on her mobility. Even if Tina shared TK’s visceral objection to the immunity card idea, she wouldn’t be in a secure position to easily opt out; the standardization of immunity card surveillance would introduce a subtle yet consequential degree of coercion into the equation. On the note of TK’s visceral reaction, past experiences may affect one’s rational judgement and interpretation of a surveillance regime. As each of our past experiences with surveillance have been unique, so too will be our attitude toward new surveillance. When I asked TK’s general opinion on the topic of surveillance, the train of response went from surveillance to Big Brother to the government to the patriarchy to her not-so-great experiences with male supervisors in the military. These things are all associated in TK’s mind, and so when presented with a new form of government surveillance, these associations and all their emotional complexity, to her own admission, influenced her reaction. She was also considerably less concerned when confronted with the surveillance involving her smartphone and social media apps, both of which she uses heavily, saying “Yeah…but at least it’s not the government. If I knew the government had my best interest in mind, I would be all for it; but I can’t know that, so I don’t trust [the surveillance].”

So, what can be learned from these details is that surveillance can be desirable to some in the pursuit of increased mobility and freedom—with exceptions and complications. Individual circumstances and preexisting states of personal agency can significantly influence whether one finds an instance of surveillance alluring or repulsive. Additionally, the mere introduction of a surveillance system, such as the proposed immunity certification, can modify the social dynamics of the population in which it is introduced. Too often such regimes are designed and implemented with little or no consideration to these complexities. It is also of great significance that, in the example of the immunity cards, the power to restrict as well as restore freedom of mobility is centralized in the state. So, while an individual experiences increased freedom from within the system, from an outside view, they’re merely being allowed a longer leash. The state commands the problem as well as the solution. That said, this need for surveillance is somewhat manufactured, and so the desire for the surveillance is arguably artificial. What of desire for surveillance that is more naturally human?

In Pursuit of Identity and Belonging

Human beings have the emotional need to identify as both unique individuals and accepted members of social groups. In modern society, surveillance practices are utilized to assess and classify—to define and distinguish individual and group identities. We desire this surveillance because we desire to exhibit our individuality and be recognized in an official capacity for our status as members of certain groups.

Consider the allure of the modern driver’s license. Of course, it is desirable as a credential that allows an individual increased mobility and increased personal freedom, but there is something more: the driver’s licensing process is a form of surveillance that functions as a modern ritual of initiation. The aspiring driver is made to complete a series of challenges while being observed by an individual acting in an official capacity. If the aspirant’s performance is deemed sufficient, they are officially licensed, registered, and identified as a driver by the state—they step into the identity of a capable driver and are publicly recognized as a member of the group of licensed drivers. The driver’s initiation is particularly significant to many because it can also signify passage into young adulthood; comparable processes can be seen elsewhere such as in academia or institutional marriage. I have observed relatable phenomena during this pandemic.

A friend of mine recently had someone come by his house to give him a haircut while I was visiting (imperfect social distancing, I know—it gets worse). When the hairdresser arrived, I instinctively reached out and shook his hand to introduce myself. I realized my faux pas immediately and said, “Oh, I’m sorry—we’re not supposed to do that,” to which he replied dismissively, “Whatever, I think I’ve already had it.” I responded with something like, “Oh, okay then,” and I immediately went to wash my hands. While I was at the sink, I couldn’t help but feel like there was a tinge of pride in the hairdresser’s response, and I realized that this hadn’t been the first time someone seemed to actually want to believe or assert that they’ve already been infected. Admittedly, I may be projecting a bit, but it got me thinking about possible explanations.

It is reasonable to say that COVID-19 has been a catalyst for societal change—there was a pre-COVID-19 world, and there will be a notably distinct be post-COVID-19 world. At the time of this writing, we are amidst the liminal phase of this development. Since all of humanity is headed toward the post-Covid-19 state, and this liminal phase is remarkably unpleasant, is it farfetched to think that it could be desirable to have arrived on the other side? Assuming the disease is a one-time thing, what better goalpost than knowing you’ve already recovered from the infection? The surveillance of being tested or vaccinated could provide meaningful certainty that the worst is in the past, providing freedom and refuge from the liminal state of not knowing. Additionally, to verify that one has overcome a potentially deadly, global threat is not insignificant; it symbolizes strength and fortitude as well as a hint of exclusivity—of being a bit of a trailblazer. On the other hand, if the test is negative, one gets to identify as having (at least, so far) evaded the threat. Without the surveillance, we’re trapped in not knowing where we stand nor, in this sense, who we are.

I relayed the dismissive claims of having had the virus and my relevant musings to Xoe, a friend who likely had and recovered from the COVID-19 disease (she was denied a test despite being in hospital quarantine). She thinks the ability to claim recovery so flippantly is a “weird flex,” saying, “Like, I’m just being thankful that it wasn’t worse or that I didn’t have to see someone that was close to me suffer and die. It’s like someone who survived AIDS lording it over the people who didn’t—but, like the way people view AIDS today as more of a story than a lived experience, people are doing that with Covid. I just don’t get it.” I was reminded of the tears and the fear in her eyes when she video-called me from a hospital bed; I realized that memory was partly responsible for the distaste I felt toward those who so facetiously told me they think they’ve already had the disease. “It’s just ignorance,” I said. She replied, “Yeah, but like, it’s important to know that this disease is deadly.” Interestingly, despite being hospitalized with all the symptoms and “sicker than [she’s] ever been,” Xoe still won’t confidently claim a COVID-19 positive identity without a test. She desires resolution but says, “I just don’t know. I believe in science. Without data it’s still just…do I really have a claim? Everything is circumstantial—up for debate.” For Xoe, the surveillance of an official COVID-19 test is the only thing that would settle this uncertainty.

In admittedly less dramatic ways, surveillance can be desired and utilized for claiming one’s identity and exhibiting it to the larger world via social media. Specifically, I have observed the common theme of posturing to appear and be identified as someone who is doing the “right” things during the pandemic—wearing masks, making masks, practicing social distancing, volunteering, supporting small businesses, et cetera. The pictures, the posts, the “likes” and feedback given to others—they all act in concert to curate identities of individuals who are morally upstanding and adhering to new social norms. Michel Foucault might say this is because we have become “docile bodies” conditioned for conformity and adherence to norms by the constant surveillance under which we find ourselves in modern society, at work, at school, by law enforcement, and so on. We have internalized this constant surveillance and are now quick to adapt to environmental expectations of appropriate behavior.

Furthermore, social media surveillance is also used to identify those who are deemed to be acting inappropriately. They are shamed and classified as outside of the group of the morally upstanding through comments, downvotes, and negative hashtags like #covidiot. Personally, I find myself closely tracking and monitoring some of my peers who have expressed views that I find concerning or questionable. This is an important point with Foucault—in many ways, we don’t need hierarchical forces to punish and discipline. We endeavor to discipline ourselves and each other, and those in power need only to control the standard narrative. Nonetheless, many individuals do not wish to conform, and they use social media in similar ways to assert their dissent.

I see this as the true allure of modern social media surveillance—a user is free to create their own narrative and identity with minimal restriction, share it with the world, and receive validation. That validation is what makes it so addictive. Humans need to feel valued and accepted, and it feels really good to do so under one’s own terms. Social media surveillance makes this possible. During the pandemic, do-gooders get to be seen doing good, rebels get to be seen rebelling, conspiracy theorists get to be seen theorizing conspiracies, and there’s plenty of room for those who wish to pretend to be such people when they are not. Of course, the lack of verification is partly why some forms of surveillance are deemed more legitimate by society—the name and gender on your license will override your name and gender on Facebook in many circumstances. The strict regulations of more institutional forms of surveillance are just more reasons why the freedom of social media surveillance is so appealing.

So, surveillance can be desirable because it allows us to know where we stand as individuals and where we fit into society. It can validate and legitimize our status, roles, and abilities, and in some instances, allow us to freely create and explore our identities as we wish. Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that surveillance can also be used to reduce and classify individuals and social groups in ways that can be harmful. Close attention and respect should be given to the individual circumstances of any specific application or use of surveillance to truly understand the forces at work and their consequences.

Conclusion

It is my hope that this exploration of surveillance through its potential to be desirable provokes readers toward reconsideration of their own preconceived ideas and assumptions about what surveillance is and what it can mean. Surveillance is not a dull, lifeless process existing only to spy and control. There are whole inner worlds of symbolic relation to surveillance; there is a culture of surveillance. Surveillance means different things to different people at different times, and its effects are broad and penetrating. The more people know and understand what is going on within and around them, the more personal freedom and agency they may have in their lives. The better people understand the motivations and intentions behind surveillance and the reasons for their own surveillant desires and aversions, the better equipped they will be to make wise decisions regarding the practice. Surveillance is ubiquitous in modern life; knowledge of the topic and awareness of one’s personal relation to it can only serve to empower. While in some ways it is resisted and in other ways it is welcomed, surveillance is always meaningful.